Take an elevator up three floors in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, and you’re inside UrbanGlass, one of the coolest glass studios in the world. At over 17,000 square feet, it’s enormous, and its shops are arranged into a circle, each open door emanating light, heat, and the noise of craftspeople.

UrbanGlass, photography by Ryan Muir.

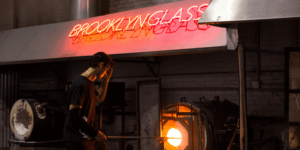

In the Cold Shop, artists wearing headphones hone in on tiny details while grinding and sanding near-finished works of glass down to perfection. The Neon Shop gives artists the chance to bend long tubes into shapes and words, before specialized equipment fills them up with glowing gases. (Fun fact: Every bona fide neon sign you’ve ever seen was made and shaped by hand.) In the Mold Shop, artists craft molds out of items from the real world, then create plaster silica molds around wax to cast them in glass in the Kiln Room. In the Flat Shop, artists work with prefabricated sheet glass on stained glass and other fused works. Rows of lockers dotting the walls are filled with artists’ and students’ materials.

In the Hot Shop, artists work with molten glass removed from a furnace that stays on 24/7 to keep the glass in liquid form. “Imagine a bathtub full of honey,” says Kellie Krouse, UrbanGlass’s Registrar. “It’s like that, but the glass is heated to around 2,100 degrees.” Ten reheating chambers allow the incandescent process of heating, shaping, blowing, and cooling glass to go on at each artists’ pace.

Krouse was completing a ceramics degree at NYU when she first attended a beginner’s survey of different glassmaking techniques offered to NYU students at UrbanGlass. Glass, she assumed, was kind of like ceramics. “After two weeks, I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is the coolest thing ever,’” she said. She took another class, focused on a specific project. Then she retook both classes again. “I was just always there,” she says. “I just loved it, loved the class, loved the art, and especially, loved the studio.”

After graduating, she nabbed a part-time job, then became a studio technician, then settled into her full-time job as Registrar for the studio’s Education Department. Krouse also sells the glass artwork she makes at UrbanGlass — making her another of a generation of artists born at the public access glass studio and nonprofit organization.

UrbanGlass is not just a glass studio located, improbably, on the third floor of the former Strand Theater in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. It’s an institution, an affordable, accessible studio for glass artists new and old alike, and an on-ramp for the future of glass artists, craftspeople, and enthusiasts.

A glass studio grows in Brooklyn

The studio had been around long before Krouse discovered it as a hopeful student. It was founded in 1977 by Erik Erikson, Richard Yelle, and Joe Upham, three recent art school grads who wanted to continue their experimentation in glass work. From the beginning, The New York Experimental Glass Workshop was a place for education and access to the heavy machinery and tools required to work with glass.

The studio grew over the years, gaining recognition thanks to the famous glass artists who called it home — like Dale Chihuly and Toots Zynsky — and its quarterly publication, now called GLASS Quarterly. The studio moved to its current location in 1991, and grew to its current size after a $62 million renovation funded by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs was completed in 2013. To install new furnaces, a hole was cut into the side of the building, and each furnace was lifted by crane into its new home.

A one-of-a-kind studio

Most people don’t imagine a glass studio could exist stories above the ground. Though it’s located on a busy Brooklyn thoroughfare, though over 350 artists work there frequently, “most people don’t realize it’s up there,” Krouse says.

Even more surprising? How easy it is to get involved. The studio offers a number of introductory classes on many glass art techniques, plus topics like entrepreneurship. There is no membership fee or dues; everyone, from legendary artists to those just starting out, pay an hourly rental fee to access the space. Krouse estimates the community to be about 50% artists, 50% students and other non-professionals. “We have the equipment, you bring in your supplies and your glass,” Krouse says. “We have a lot of artists who kind of just run their businesses out of our studio.”

And that’s not all. The ground floor of the studio serves as the gallery and store front where artists’ works are showcased and sold. Through annual open calls, any glass artist can apply for their art to be sold or shown in the Window Gallery — just the kind of thing, say, a young up-and-comer needs to make their first mark in the industry.

The huge range of tools and artists means all sorts of glass artwork comes out of UrbanGlass. Krouse’s line “Soldered Curves” explores the female body using stained glass. “I do a lot of work that has to do with the body or just our physical existence in the world,” she says. “I make these soft, squishy, movable things into permanent, hard, fragile and yet strong things.”

A special kind of community

Glass art is inherently a team sport. Most projects require at least one extra set of hands, if not many. “It’s a community-based technique, and with glassblowing especially, you can almost never do it by yourself,” Krouse says. “We are really proud at UrbanGlass of our community — how strong it is, and how long we’ve been going. There are people who have been involved with UrbanGlass over 40 years, and they have no plans of leaving anytime soon.”

Though the studio is open and easily accessed, before working on their own projects, new members can take classes and learn safety procedures. Because UrbanGlass houses so many different shops and tools, an amateur glassworker can learn a wide range of techniques, eventually settling into their favorite to hone their skills.

A number of programs are aimed at bringing fresh blood — particularly among underserved communities — to the studio. One, The Bead Project, has been running for almost 25 years, giving financially disadvantaged women the opportunity to learn bead-making alongside the entrepreneurial skills to sell their wares. (An alumni of the program, Opeyemi Omojola, made work recently featured in Vogue.) The studio is also a frequent site of collaboration between artists seeking glasswork elements for sculptures and other installation art.

For her part, Krouse and the Education Department have defined five “pillars” of a mission statement: They want to welcome, inspire, instruct, nurture, and propel students. “In summary, we want to give this space for people to come in, learn, and expand, and then provide opportunities to launch from there. There are definitely obstacles to it. It’s expensive, it’s time consuming, it takes a long time to learn. So we’re still constantly trying to figure out the best ways to do that.”

Krouse knows this process intimately. When she first came to the studio, three hours once a week for her first class, she remembers seeing artists around her doing “crazy, inspiring” things. “I was just a little 19-year-old student going, ‘what is that?’ And people would take the time to answer and show me what they were doing.”

Now, Krouse gets to know every new student and artist that works at the studio. She enjoys watching them go through the same range of emotions she once did: wonder, awe, curiosity. Eventually, some of these new students have a revelation while watching other glass artists make a living: Wow, this is possible. “Watching these artists use techniques that took 20 years to develop, being right in the middle of the field, that’s just something you can’t replicate,” she says.

Interested in attending one of UrbanGlass’ events? Follow them on Eventbrite to be alerted when new events are added.

Up next: Read our creator spotlight on how Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works sparks new ideas and unusual collaborations.