Skift Take

The recent Consumer Electronics Show had some of the most comprehensive health and safety measures ever provided by an event of its size. But CES' failure to report the number of Covid cases detected in Las Vegas is drawing criticism and raising an important question for planners about whether events have an obligation to report cases to the general public.

Early on in the pandemic, many saw the widespread availability of reliable Covid tests as a key factor in ending the pandemic. And as early as July 2020, event organizers were experimenting with using rapid antigen tests to screen attendees at the door. Now, almost two years into the pandemic, has that early promise been fulfilled?

CES 2022, an event that provided rapid testing kits to every single one of its roughly 40,000 attendees — with the option to retest if symptoms should arise — could be hailed as an example of how far we’ve come. Its testing program, however, has not escaped criticism. More specifically, some are calling for CTA (the Consumer Technology Association, the organization behind CES) to disclose the number of positive Covid cases detected through the event’s onsite testing. When approached for comment, CTA provided the following statement:

“We don’t have confirmation of the number of cases as it is extremely difficult to determine exactly when and where anyone contracted COVID-19. Results from testing done onsite by medical staff were reported to the local Southern Nevada Health Authorities.”

While this statement is brief, it implies a great deal about the purpose and scope of onsite testing at events. Most notably, it shuts down the idea that onsite testing could provide insight into the probability of becoming infected at an in-person event. Just because an event’s testing program detects a case does not mean that the infection was contracted inside the event’s venues — even if the test is performed several days into the event.

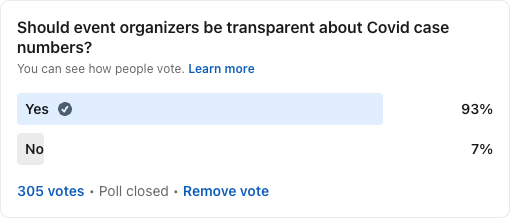

A recent LinkedIn poll on this very topic indicated a strong desire from the 305 event professionals who responded. 93 percent voted in favor of transparency around Covid case numbers from event organizers.

The Rationale for Onsite Testing Has Shifted

While the data may not be perfect, some argue that the numbers could still provide a general ballpark idea of how much spread occurred at the event itself.

Adrian Segar, founder of Conferences That Work, believes that better transparency around Covid case numbers at events could help meeting planners understand the degree of risk involved:

“The crucial issue is that we all want to have the best information possible. If we hold an event with certain precautions, what’s the likelihood that cases will arise from that event? There’s no way we’re ever going to have a perfectly accurate answer, but we can get an idea. That’s really valuable for meeting professionals. And it’s also valuable for the public and our whole society to know that kind of information.”

– Adrian Segar, founder, Conferences That Work

To provide a clearer picture of how much the event itself can be held responsible for cases detected through its own testing, one strategy is to compare the attendees’ rates of infection on follow-up tests against the percentage of cases in the general public. This was, in fact, the approach that early “event experiments” in Barcelona took when trying to assess the safety of in-person events — and a series of other government-backed event programs across the globe followed similar models.

At CES, follow-up testing would not even be necessary to get a sense of potential transmission at the event; CES was a multi-day event, with tests available throughout the duration. The main difference now is that large-scale event organizers (like those behind CES) are not testing with the intention of proving that in-person events are safe. Their testing programs are more about risk reduction than risk assessment.

Ultimately, there are multiple rationales that motivate onsite testing programs, and only one of them has begun to decline over time. These include:

1. Minimizing transmission at the event by detecting cases and thereby preventing infected attendees from entering the venue

2. Having a mechanism for notifying those who may have been exposed through proximity to confirmed cases

3. Giving attendees hassle-free access to timely tests they may need for travel purposes following the event

4. Using a statistical analysis to gain a better understanding of the transmission risk involved with attending an event

The final objective on this list is losing ground, yet the motivation behind this shift is not clear. Is it because a meaningful statistical analysis is truly a lost cause given the complex mix of factors involved, or because it’s better for the industry’s public image to avoid the conversation altogether?

What Thought Leaders in the Industry Are Saying

While opinions within the event industry differ, two schools of thought emerged from our interviews:

- The belief that a statistical grasp of the risk involved is best left to government institutions, who will then set regulations on in-person gatherings based on their research

- The view that even if it means going above and beyond government requirements, there are benefits to treating in-person gatherings as case studies that help to show the degree of transmission risk involved

Arguments Against a Duty to Disclose Covid Cases

Although CTA did not explicitly state that such matters are best left to the government, they implied a similar mindset when mentioning that they reported case numbers to the relevant state authorities. (It is worth noting, however, that in many other respects, CES went well beyond government requirements in terms of its safety measures.)

Kai Hattendorf, managing director and CEO of exhibition industry association UFI, more directly expressed a reliance on government policies when designing event safety policies. After describing the government-compliant rules in place at the 88th UFI Global Congress in Rotterdam, he stated:

“Going forward, we will apply the same logic: Work with the venue and the local health authorities to ensure we apply all the regulations that are in place at the time. UFI does events all over the world, and regulations on site keep evolving in line with the progress in overcoming the pandemic.”

– Kai Hattendorf, managing director and CEO, UFI

When asked specifically about the value of transparency around Covid numbers, Hattendorf suggested that the data is too compromised to establish cause with any accuracy: “Any person can catch any infection anywhere. Statistically, these numbers will hold no value as only a fraction of participants of any event will need to be tested connected to accessing an event — with huge variations based on differing local regulations.”

In most cases, the data is in fact incomplete. Beyond the difficulty in establishing precisely where an attendee became infected, there is the issue of piecemeal testing. In the Netherlands, where UFI’s Global Congress was held, tests were required only from those who had no record of either vaccination or prior infection. Even at CES, the free testing kits made available at check-in were provided for use in private under an honor system — supervised onsite testing was only done for those who voluntarily went into the event’s health clinics following symptoms.

Jennifer Brisman, founder and CEO of VOW Digital Health, echoed Hattendorf’s position. According to Brisman, there are so many variables that influence the rates of infection found at an event, that it is misguided to think that a cross-comparison of data will yield any conclusive results without careful segmentation:

“Depending on when your event was, where it was, how large it was, will offer up a different picture. […] Data from 1 event is irrelevant; data from 1,000 across one day, within similar constants and limited variables, is.”

– Jennifer Brisman, founder and CEO, VOW Digital Health

Of course, such comprehensive data is not realistically achievable. But what does the corporate end of this equation think? Is incomplete data truly useless?

According to Ian Cummings, global head at CWT Meetings & Events, most corporations are not particularly concerned with the data coming out of events after they’ve transpired — whether the findings are reliable or not. Instead, their focus is on a combination of general case numbers in the destination and prior research:

“Corporates aren’t pressing event organisers for covid case data. There is an abundance of data available from most Gov websites, research companies and consultant publications. We are able to support and supplement with our own data hubs built around our safe return strategies for our clients — but most companies have already done their own research prior to engaging with the event planners.”

– Ian Cummings, global head, CWT Meetings & Events

Further, most corporations are likely testing their employees post-event with the assumption that exposure was a risk.

Arguments for Transparent Reporting of Covid Cases at Events

While none of our interview sources directly criticized CES organizers for failing to disclose their case numbers, some did suggest that there is room for some events to position themselves as case studies for the industry.

Sherrif Karamat, CEO of PCMA, was diplomatic in his handling of the controversy. “Reporting is good if it serves a purpose. Reporting can also be bad if it just creates hysteria,” he said. In particular, he believes that a duty to report cases applies primarily to events where vaccination is not required for entry:

“If event organizers are going to choose not to have vaccination as a requirement, I would then say that it’s important to report the incidents of Covid because there’s more chance that someone could become seriously ill. And it’s important that people get help as quickly as possible should they have been exposed.”

– Sherrif Karamat, CEO, PCMA

This argument is essentially the view that an event organizer’s duty of care is limited to two objectives: preventing spread at the event and notifying attendees of potential exposure.

Karamat’s own organization, however, chose to publicly disclose the case numbers from its vaccine-mandatory Convening Leaders event — even making an effort to track cases post-event. “Because we wanted to show that events could be done safely, we took the policy that we will be open about the numbers,” he explained. In other words, this approach is advisable for those who actively want to contribute to a better understanding of the wider risks involved. This view suggests that such efforts are not so much an ethical requirement as a bonus service to the industry.

Karamat was also transparent about the fact that only some of Convening Leaders’ participants were tested. Rapid antigen tests, rapid molecular NAAT LAMP tests, and rapid PCR-RT tests were all made available to attendees for a fee, and a total of 130 out of 2,391 onsite participants chose to take a test. Of these, only eight tested positive at the event itself.

Paul Van Deventer, president and CEO of MPI, had a similar perspective. For both the 2020 and 2021 iterations of MPI’s World Education Congress, his organization chose to disclose all potentially related Covid infections — tracking cases for a full 14 days after the event, beyond the 10-day window that the CDC had recommended at the time.

Van Deventer, however, noted that these events took place at a time when in-person gatherings were only beginning to return:

“When we were all coming to terms with the implications of the pandemic, we made a commitment as an organization to understand how to put the safety and wellness of attendees at the forefront. We did execute two large in-person meetings deep into the pandemic when a lot were being canceled.”

– Paul Van Deventer, president and CEO, MPI

Like Karamat, he suggested that these efforts were not so much a basic requirement as an instance of going the extra mile to bring the industry forward. “We looked at those two events as establishing case studies and best practices. Maybe in some ways we went over the top in our steps, as well as in our communications and our reporting afterwards,” he explained.

IN CONCLUSION

If there was a common thread among our interview sources, it was that some level of risk is inevitable — particularly in the context of the added transmissibility of Omicron.

While they all agreed that it’s important to let attendees know if they have been exposed to Covid, some suggested that attendees should take the possibility of exposure for granted at an event of CES’s size. “If someone was attending CES and did not go there with an understanding of how high risk it was for them to contract Covid, I think they may have been naive,” Van Deventer commented.

From a public health perspective, the relative degree of transmission that occurred is still relevant. Those defending CES would say that reporting numbers to government officials is sufficient. Whether the wider public would agree is another matter — but at least for now, the debate seems to be fairly confined to those within the event industry themselves.